A world of self-driving vehicles and mobility-on-demand is likely to exist eventually, but for the next decade, widespread implementation of autonomous technology will not be realized, according to a new forecast from S&P Global Mobility. In that timeframe, researchers say that autonomous technology for passengers will be limited to two specific areas: geofenced robotaxis operated by fleets in specific areas, and hands-off systems in personal vehicles that will still require some form of driver engagement.

The analyst firm’s latest forecast notes that SAE Level 5 autonomy, involving “a vehicle that can go anywhere and do everything a human driver can,” will not be publicly available before 2035, “and probably for some time after that,” said Jeremy Carlson, Associate Director for the Autonomy Practice at S&P Global Mobility, who gave Inside Autonomous Vehicles a sneak peek of the latest quarterly research. “But the outlook for more targeted implementations of the same fundamental technologies, especially in Level 2+ and Level 3, but also for some forms of Level 4, is more positive and will certainly happen on a much shorter timeline.”

Its latest outlook reflects the slower pace of development that both the auto and tech industries have demonstrated over the past several years—in stark contrast to the optimism of just five years ago when the world was swept up in the promise of a future of Levels 4 and 5 self-driving vehicles. Now, S&P Global Mobility presents a more realistic outlook amid this moderated pace of progress while also publishing new data on the intersection of autonomy and mobility-as-a-service (MaaS).

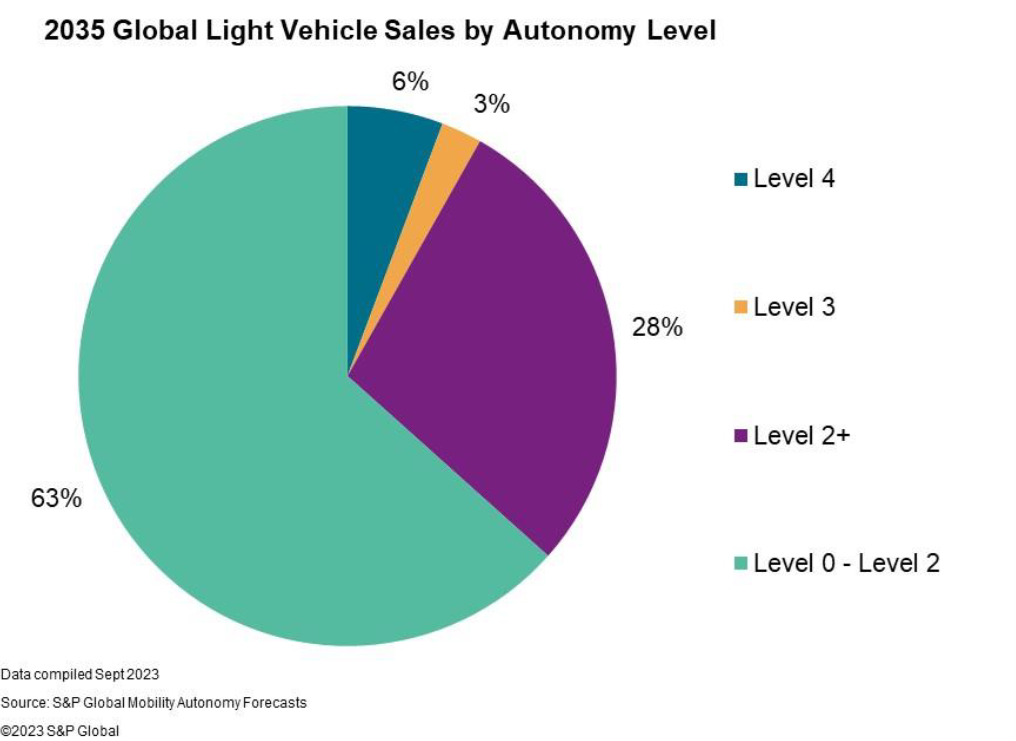

Automated, rather than autonomous, driving continues to be the primary focus of industry development. Broad deployments of Level 2+ and Level 3 automated driving systems by many automakers in multiple regions will reach at least 31% of new vehicle sales globally by 2035, according to the forecast. The L2+ and L3 systems allow drivers to be hands-off while supervising, such as in General Motors’ Super Cruise, or to disengage entirely in specific driving scenarios, as with Mercedes-Benz’s Drive Pilot.

“There is immense opportunity for automated driving systems in L2+ and L3, and they are benefiting from the standardization of basic safety features, which provide a foundation of in-vehicle architecture, sensing, and compute,” said Carlson. “Their functionality also complements driving today rather than fully replacing the driver, making consumer adoption less of a challenge. The next several years of wider deployment across brands and vehicle platforms will be a boon for automakers selling these optional features as well as suppliers who continue to build scale and a strong foundation for the future.”

The forecast predicts fewer than 6% of light vehicles sold in 2035 will have any Level 4 functionality, with early implementations in personally owned vehicles offering advanced parking functions often with the support of infrastructure.

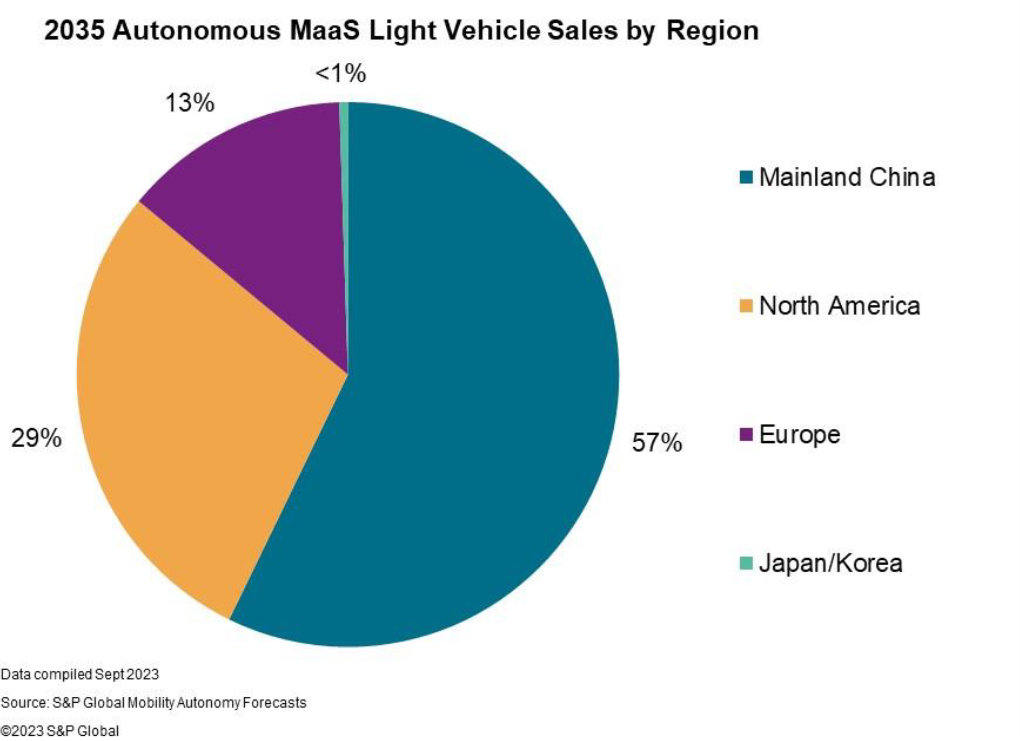

However, technology providers remain focused on the long-term potential of scaling AVs in fleets supporting MaaS business models. Carlson cited positive examples of AVs performing as well as humans in pilot programs in places like San Francisco and Phoenix in the U.S. and in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou in China.

While MaaS vehicles and robotaxis can still be confounded by complex traffic scenarios, giving regulators and consumers reason to be cautious, they are expected to lead the transition to an AV future, but with relatively cautious growth ahead. Forecasters do not expect the growing number of small-scale deployments in certain cities around the world to become widespread and broadly accessible within the next decade. They expect applications to represent less than 800,000 vehicles sold globally in 2035.

Robotaxis will be carefully geofenced for the foreseeable future, offering revenue service only within specific areas where they have already been extensively tested, Carlson predicted. However, he said that their high utilization rate can be effective at bringing new mobility options to some consumers and new revenue streams to automakers and mobility providers.

In August, the California Public Utility Commission approved the expansion of operations in San Francisco for Waymo and Cruise. Chinese regulators are also enabling providers like Baidu’s Apollo, Pony AI, and WeRide to test or operate paid services in parts of many major Chinese cities. Europe is developing regulations to help bring some uniformity to such vehicles and services across the region.

While the U.S. captured an early lead in both development and deployment of Level 4 MaaS, S&P Global Mobility expects China to contribute the greatest volumes in the long term, followed by the U.S. and Europe in that order.

Challenges remain for successful and widespread deployment of Level 4 MaaS. In addition to a fragmented regulatory landscape and relatively low public trust that may hamper consumer acceptance and adoption, the cost of technology and the time needed for robust development and validation of hardware and software have proven more challenging than expected in the past decade.

The reduced complexity of L2+ and L3 features present less risk or uncertainty for these factors, hence the more positive outlook of researchers for those technologies in the short term. This optimism is further boosted as some regulators are also mandating certain basic safety assistance features that will generate wider exposure for selective automation.

“There’s still a huge amount of opportunity that we’re seeing in L2+ and L3,” Carlson concluded of this most recent quarterly study, which was more about MaaS. “But it is also relevant because it means we, especially the supply chain, don’t have to wait for volumes to materialize for autonomous mobility. They’re still going to have quite a bit of growth in what they’re doing here for the near term, just in a different form and potentially with different partners.”