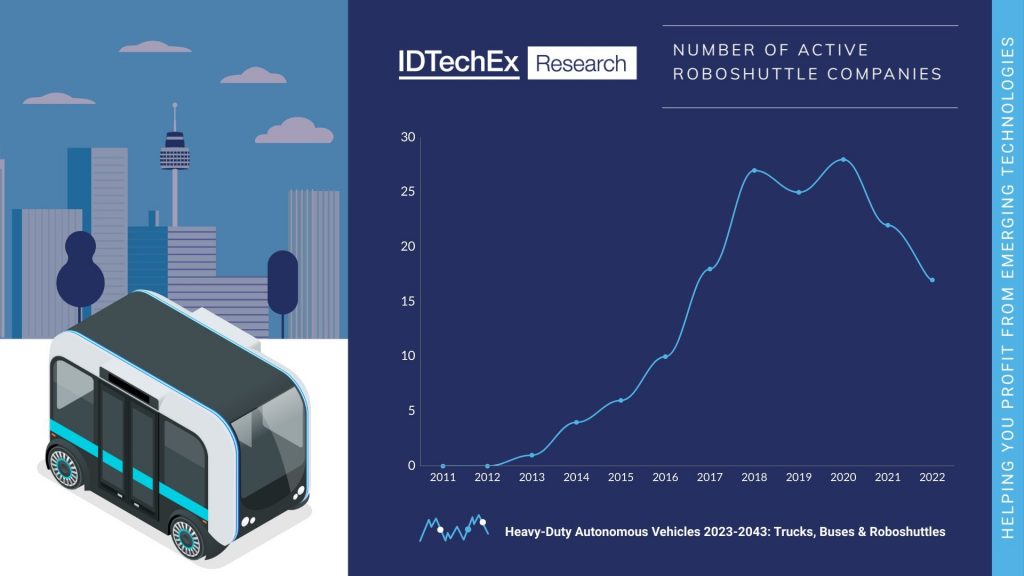

A new analysis suggests that roboshuttle sales are declining, as are the number of active companies working on them.

Roboshuttles like those from EasyMile and Navya are typically all-electric vehicles, autonomous, and a promised solution to last-mile journeys in cities. (In logistics, the last mile refers to the trip to a customer’s doorstep.)

However, a new report from emerging technology analyst firm IDTechEx in Cambridge, England, found that Navya reported declining sales since a peak in 2018, when it sold more than 60 units. Last year it sold just 19. Other roboshuttle companies have had to close shop.

“COVID has certainly had some impact on the industry,” IDTechEx technology analyst James Jeffs said in a blog post on Sept. 28. “Social distancing measures and other cautions made testing any autonomous transport very difficult in 2020.”

Starting at the end of 2021, autonomous trialing and testing activity resumed. This allowed robotaxis to start commercial deployments with fleets of up and hundreds of fee-charging vehicles in operation. However, the same recovery was not seen in the roboshuttle industry, with new trials remaining small and supervised, Jeffs noted.

The roboshuttle industry faces three major hurdles before it can see commercial deployment, Jeffs noted. The first is “homologation”—a homologated vehicle is one that has passed numerous roadworthiness tests, design specifications, and minimum equipment requirements to verify and validate that it will be safe.

“When robotaxi companies, autonomous truck companies, and autonomous bus companies retrofit to vehicles, they are working with homologated vehicles,” Jeffs noted. “This means that the authorities have no concerns about the vehicle being road worthy and only need to worry about the new autonomous systems.”

In contrast, roboshuttles are not homologated. They are built from the ground up to be autonomous, which means they lack conventional driving controls, such as a steering wheel and pedals, as well as other key features that normally make vehicles roadworthy, such as wing mirrors.

“This means they require additional exemptions to be allowed to test on the road,” Jeffs noted. “Exemptions are used in most autonomous testing to allow work-in-progress autonomous systems to prove their safety during on road testing. Laws are also changing and evolving to allow such vehicles to operate commercially now that they are proving their safety. The difference for roboshuttles is they also need a separate set of rule changes that will allow them to operate vehicles on public roads without conventional controls and other human-driver necessities.”

Autonomous delivery startup Nuro is also building vehicles that are not homologated that are currently in commercial trials, making paid deliveries to people’s houses in California, Arizona, and Texas. However, its small machines are designed to only carry goods, easing its advance—the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) recently ruled that zero-occupant vehicles do not need features designed to protect occupants, such as seatbelts and airbags. In contrast, roboshuttles will be carrying occupants, and the regulatory challenges they therefore face present obstacles to commercialization.

A second hurdle roboshuttles face is proving that their autonomous systems are safe. Major players in the robotaxi industry, such as Google’s sibling Waymo and General Motors’ self-driving subsidiary Cruise, have fleets of hundreds of vehicles that have amassed millions of on-road miles of testing in California alone. In contrast, roboshuttle fleets are typically smaller and only test on routes 1 to 5 kilometers large, making it much harder for them to prove their safety.

“Furthermore, without conventional controls for a safety driver to sit behind, regaining control of the autonomous system is also more complicated,” Jeffs noted. “Test drivers will typically use a remote-control box, with a joystick for controlling movements and buttons to override or stop the vehicle. This limits the speed at which the vehicles can be tested, with 25 kilometers per hour being a typical limit imposed.”

Slow vehicles, short testing routes, and limited fleet numbers all mean that both the development and proving of the autonomous system is going to be slower for roboshuttles than robotaxis.

Finally, it remains uncertain what purpose roboshuttles will have. “The use case for robotaxis is clear—Uber has been shown to be incredibly popular, and a driverless version promises to be cheaper and safer,” Jeffs noted. “For autonomous trucking, it is simple—there are presently not enough truck drivers, and autonomous trucking on freeways between distribution hubs is quite achievable. But what will be the purpose of roboshuttles?”

Roboshuttle companies often paint a picture of these vehicles fulfilling the individual routes of passengers. “But they will be competing against a well-established public transport system of buses, trains, metros, and trams in whatever city they get deployed in,” Jeffs noted. “Not to mention cycling and walking, which already account for a large proportion of final mile journeys.”

Given the small trial demonstrations of roboshuttles to date, IDTechEx said it was not certain how these new vehicles might get adopted into public transportation systems. “They could be a much-needed solution to final mile journeys, or they could be another vehicle cluttering the already busy roads,” Jeffs noted.

Still, there remains interest in roboshuttles. For instance, while Cruise largely works with passenger cars, its long-term ambition is to operate using a specialized autonomous roboshuttle-type vehicle called the Origin.

“GM and Cruise are already planning the production of these vehicles, and with their financial might, it would be ill-advised to bet against them,” Jeffs noted.

The Cruise Origin will face problems with homologation, as it is designed without conventional controls, exterior mirrors, and so on. “Cruise has been petitioning the NHTSA for approval to deploy the unconventional vehicle, but there does not appear to have been progress here yet,” Jeffs noted.

However, when it comes to the other hurdles, Cruise has some advantages. It is already demonstrating its capability in autonomy, and also has a use case planned in the form of a robotaxi-like service, carrying up to six people and able to achieve higher speeds than the likes of EasyMile and Navya. “The downside to this is that it will come at more of a premium than the public transport-oriented competition,” Jeffs noted.

Another major player includes automotive systems company ZF Group, which recently acquired shuttle maker 2getthere. It is working on an autonomous roboshuttle version of 2getthere’s GRT, and has sensors such as radar and LiDAR that it can add to the vehicle.

“The vehicle has already been deployed on trials,” Jeffs noted. “ZF will still need to homologate the vehicle and show that its autonomous systems are up to scratch, but it does have good ideas for deployments.”

For example, ZF has previously spoken about transforming disused railways into dedicated roadways for its vehicles. “This would be cheaper than recommissioning a railway, easier for the autonomous system by better controlling its operating environment, and might even get around some homologation issues by operating off public highways,” Jeffs noted.